Gloucester Square, as with much of the Hyde Park Estate, stayed, for the most part, visually consistent throughout the 19th Century and the first three decades of the 20th Century, as demonstrated by Aeriel Photos of Gloucester Square from the late 1920s:

Side note: We are fortunate that the Hyde Park Estate was well documented by Aerial Photography services during the 20th century, now catalogued by Historic England. You can a view chronological list of these photos on our dedicated page – 100 years of Aerial Photos.

By the 1930s many of the Houses on the estate had reached, or were nearing, the end of their 95 year leases, and these properties often fell back under the control of the Freeholder, namely the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, as the Church Commissioners were then known. As their Consultant Planner, Leslie Lane, wrote in her 1973 Article concluding the Country Life Series on Tyburnia, there was no master plan for the Estate in the interwar years, leading to an introduction of great architectural variety, in lieu of consistency. Gloucester Square was no exception, with most of the original leases granted for 94 3/4 years from Lady Day, 1843.

In terms of broader economic drivers, there were two competing trends at the time.

The first was an ever increasing demand for accommodation in Central London, with the conversion of large houses into flats being seen as a key mechanism for meeting demand, as was discussed on more than one occasion at the House of Commons. Indeed the Housing, Town Planning, etc., Act of 1919 gave increased powers to leaseholders to convert their houses into flats, even where restrictions in the given house’s lease or restrictive covenants would prevent such a conversion.

Secondly, the market seemed desirous to move away from these Grandiose White Stucco Houses, with large heating and maintenance costs, towards more compact and efficient townhouses.

The combination of the contractual position of Houses on the estate, and these broader market trends, brought great changes to the square between 1932 and 1937.

Conversion of 13-14, 26-28, and 45-46 (now 48-49) Gloucester Square

On Gloucester Square the majority of houses were granted Leases running for 93 and 3/4 years from Lady Day 1843 (expiring at the end of 1936). Though there were some developments prior to this.

The first houses we can evidence being converted to flats are 13 and 14 Gloucester Square, with plans submitted by Harold R Luck on behalf of W Harrisson, approved by Westminster in March 1925. The original lease for 13 Gloucester Square was surrendered on the 19th of June 1926, and presumably replaced with a development lease or leases for the individual flats.

The houses 45 and 46 (now 48-49) Gloucester Square, had already been combined into a single property at some point after 1880 under the ownership of Henry Lucas, the only such combination we are aware of on the Square. It is for this reason there is no dividing lines between the properties in the 1893 Ordinance Survey map we use for our Interactive Historical Map. A few months after his application at 13-14 Gloucester Square, Harold R Luck applied for permission to convert 45-46 Gloucester Square into flats, this time on behalf of Mr E B Montesole. The initial 1925 application was rejected, though a 1927 application was successful.

The 1924 Boyles Guide does not list these properties (13, 14, 45 & 46), implying they were vacant and either primed for, or actively undergoing conversion into Flats. The 1931 Boyles Guide suggests the conversion into flats was complete, with 4 family names listed against number 13, and 2 family names listed against both 45 and 46 Gloucester Square, meanwhile 26-28 was blank, suggesting it was about to join the trend. The RIBA Library still retains records of proposed alterations to the third floor flat of 26-38 in 1940, supporting the assumption it had already been converted at least several years prior.

Of the remaining conversions: 21 Hyde Park Square, 41-43 (now 44-46) Gloucester Square and 44 (now 47) Gloucester Square were all converted by 1952 – as evidenced by the dotted lines between the houses in the 1953 OS Map (surveyed the prior year). However it is not clear whether some of these properties were converted pre-war, as we suspect.

By 1937, many other houses on the square, rather than be converted, would be knocked down and replaced with more efficient townhouses.

1-9 and 31-37 Gloucester Square – 1937

The most prominent of these redevelopments would be the houses at either end of the Garden, formerly 1-8 Gloucester Square, and 32-37 Gloucester Square, replacing the homes built by William Norsworthy, that as we covered two articles prior, were considered revolutionary by architectural historian Dr Gordon Toplis.

Having demolished the original houses, the new homes were built by the Glocester Development Company Limited. Little is known about this company, though it was likely a joint venture between the builder and the freeholder. The builder in this instance was Messers Gee Walker and Slater, Limited – though the building advertisement hung from No.2’s balcony after completion, simply read “GEE”.

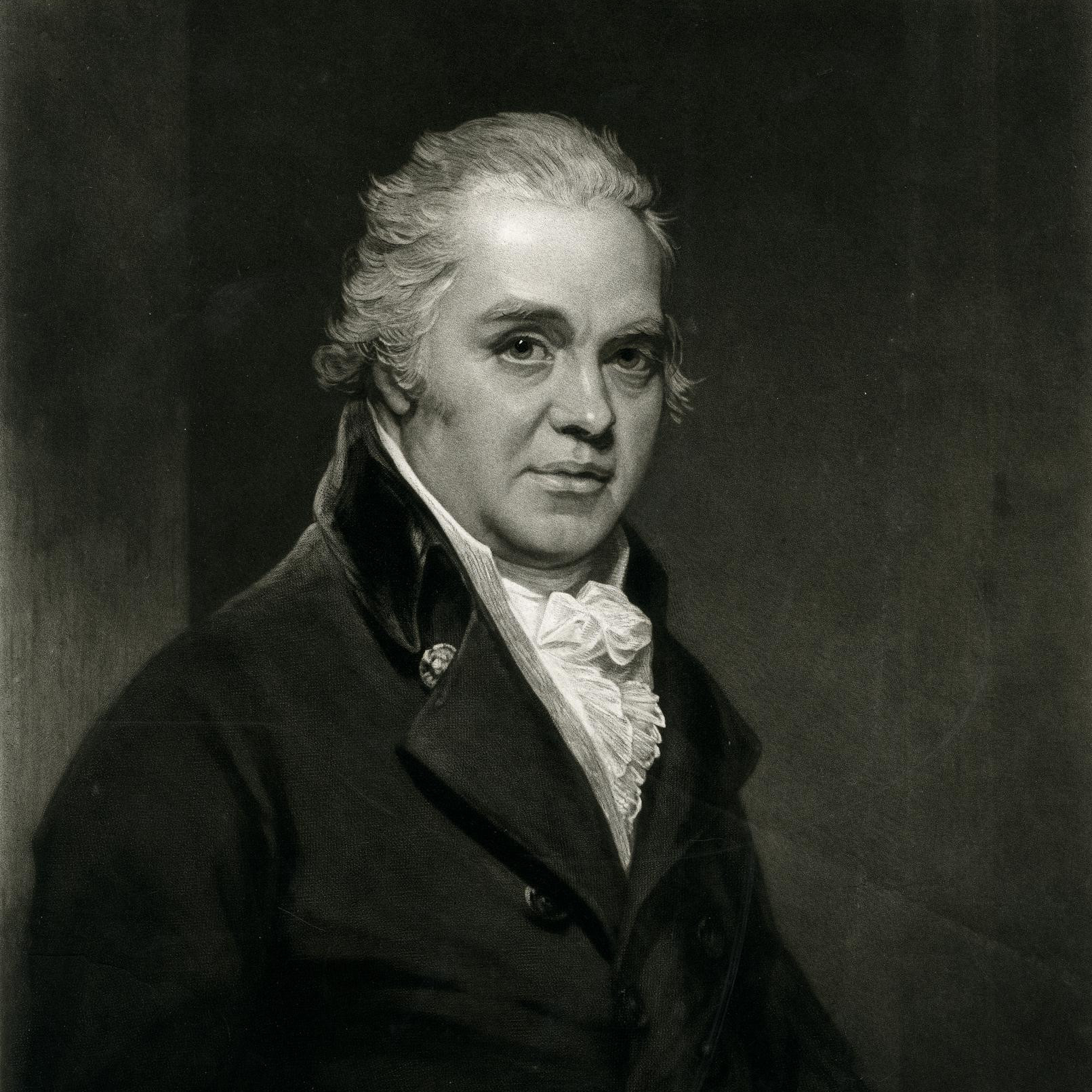

This development was the design of Architects Messrs T.P. Bennett, FRIBA and Sons. The founder, Sir Thomas Penberthy Bennett, who was in his late 40s at the time, was a Director in Glocester Development Company Ltd, and a signatory on the newly issued leases. As such, he likely oversaw the design of these townhouses, despite being a relatively small project given his stature in the industry at the time. His practice still exists today, and is known for its work in the local area including:

- The fit-out of the Royal Lancaster Hotel, including the Looking Glass Restaurant – the building itself was designed by Richard Seifert and originally intended to be an Office Block before quickly being repurposed as a Hotel ahead of its opening in 1967

- The Retail Component of the upcoming Paddington Cube Project, AKA 1 Paddington Square.

An article in a trade magazine of the time (The Bulder, January 14th 1938) was eager to point out all the modern features of these houses. They were constructed of brick work, with steel utilised internally to carry the various floors and roof. Thermacoust was used between the (timber frame) walls and floors to improve sound deadening, whilst “the rooms underneath the maids’ quarters [were] protected against sound with a special system of floor construction”. It seems all of the houses were fitted with domestic lifts of varying sizes, and these were installed by Hammond and Champness. The exterior and interior of one of these houses, captured some thirteen years later, can be viewed online in the Historic England Archives, courtesy of Knight Frank LLP:

The comparative luxury of the homes was perhaps best illustrated by the provision of sleeping quarters. There was a “Best Bedroom” (why we ever switched to the term “Master Bedroom” remains a mystery), with a dressing room and ensuite bathroom. A second Bedroom, also with an ensuite, followed by 2 to 3 Guestrooms. These were accompanied by, and here comes the luxury, 3 to 4 maids rooms!

For some reason, two of the original houses by William Norsworthy were not redevloped, and would remain in situ on the eastern corner abutting number 37. It would be another 30 years before these homes were replaced by what is now 38-42 Gloucester Square, with aerial photos of the intervening period illustrating the stark contrast between old and new.

The telegraph would later write a short piece on these houses as part of the Century Markers series – the article currently sits behind a paywall and we don’t think it is worth the premium. It does, nevertheless, reinforce the significance of these houses, built by a prestigious architect, that replaced houses that were the first of a kind when built 100 years prior. They stand as testament to the changing desires of the 20th century, and increasing value buyers placed on amenity.

Radnor Lodge (10 Gloucester Square) – pre 1937

The site of Randor Lodge was previously occupied by two houses, 9 and 10 Gloucester Square. We know this redevelopment occurred sometime between 1932, when the original houses were last photographed, and 1937, when the townhouses by TP Bennet would claim the number 9, across the road. The following photo shows Randor Lodge some 35 years later.

Little is know about Radnor Lodge, including the architect – if you know more please do get in touch.

29 & 30 Gloucester Square – circa 1937

At some point prior to 1937 a series of townhouses were built on the site of 29, 30 & 31 Gloucester Square, 3 further houses to the North on Radnor Place, and the Devonport Arms Pub on what is now Radnor Mews (previously Devonport Mews) – 7 plots in total.

The three houses on Gloucester Square, that would have been a similar height to 26-28 Gloucester Square, were demolished in favour of two shorter and wider townhouses, with 1 less floor than the houses they replaced. The development included a sloped driveway at the rear, on the site of the former pub, that allowed for private offstreet parking, the first of its kind on the Square. Two further houses of a near identical style would be built along Randor Place (numbers 10 & 11). Sadly we have been unable to locate any photos of the Devonport Arms prior to its demolition.

As with Radnor Lodge, little is known about the architect or builder behind this development. However we know the development was committed-to before 1937, as the number 31 Gloucester Square would again be shortly claimed by the TP Bennet Development across the road. We also have the following Aerial Photo from May 1937 that (just about) shows the vacant plot for this development under construction.

11 & 12 Gloucester Square – pre 1937

A third style of townhouse was introduced on the site of 11 & 12 Gloucester Square at a similar time (completed by 1937). These were the only new houses that did not increase frontage, as their plots stayed the same width as the former townhouses. Like all the other 1930s townhouses, these new homes contained one less floor than their predecessors, though the top floor for these properties was built into the roof space, complete with dormer windows. They are, in this regard, architecturally distinct on the square.

Sadly as with many of the other 1930s developments, little is known about the architect / company behind the work – though if you know more, please do get in touch.

Neighbouring Developments on Southwick Place and Sussex Place – pre 1937

Whilst not part of the Gloucester Square ratepayer group, it is interesting to observe that two of the larger 1930s developments on the Hyde Park Estate occurred directly adjacent to Gloucester Square.

On the west side of Sussex Place, directly opposite the new townhouses by TP Bennet, eight of the nine original houses were demolished to make way for Sussex Lodge, designed by architect Michael Rosenauer. Completed prior to the summer of 1937, Sussex Lodge would be the only large-scale apartment block to be completed in the neighbourhood prior to the Second World War. Standing a full storey above the original townhouses, it was also the only 1930s building to exceed the height of the original buildings, bucking the general trend for less floors.

Even in our last available aerial photograph, from 1952, we can see the original house next to Sussex Lodge still in situ, diagonally across from the Victoria Pub. The styled alike extension to Sussex Lodge on this plot, must therefore have been erected at least 15 years later. The extension retains a dedicated entrance to this day, delineating itself from the original block of flats.

In stark contrast to the heights of Sussex Lodge, on the opposite side of the Square, things were getting a whole lot shorter.

To the east, along Southwick Place, all but one of the original houses were demolished to make way for a series of townhouses. The one remaining house was 3 Southwick Place, that would become, or perhaps was already, part of 21 Hyde Park Square. Theses new townhouses are of particular note as they were by far the shortest to be constructed in the area, with only 4 floors including basement, compared to the 6+ floor townhouses they replaced. The modest designs were by Architect Septimus Warwick, and a world apart from the large buildings for which he is remembered, such as the Wellcome library.

Today, the start contrast between the 1930’s 4 Southwick Place and 1830’s 43a Gloucester Square (previously 3 Southwick Place), provide perhaps the greatest illustration of the evolving tastes of the early 20th century. Gone were the double height ceilings on the first two floors, and gone were the bedrooms up 4+ flights of stairs.

Similarly styled homes would be constructed along Stanhope Terrace, Bathurst Street, and the West Side of Sussex Square, but few such redevelopments were completed prior to World War Two. As the previous aerial photo shows, even as late as 1952 these streets lacked the visual aesthetic of a consistent row of compact townhouses, completed on the South Side of Southwick Place by 1937.

One final attempt at development before WW2 – 1937

In October 1937, Septimus Warwick, drew up plans for two new townhouses on the three plots of 23, 24 & 25 Gloucester Square, part of the site now occupied by Chelwood House. These plans can still be viewed at the RIBA Study Room in the Victoria and Albert Museum. The plans were for two townhouses, that at four storeys each would have followed the style of Warwick’s townhouses on Southwick place. The new homes would have been of limited architectural merit and quite modest compared to what was being built on other plots, and at least one storey shorter than anything else on the square. There were no:

- Balconies or full height first floor windows looking out towards the Garden, unlike TP Bennett’s Townhouses and those built at 11&12

- Off-street parking, as included in the design of 29 & 30 Gloucester Square

- Provision for Best Bedrooms with large dressing rooms and ensuites, as present in the TP Bennett Townhouses

Perhaps the plans never won approval, perhaps the Freeholder abandoned the plan, what we do know is that they were never built, and whilst we mean no disrespect to Septimus Warwick, for that we can only be grateful.